Ask a viticulturist: Unexplained splitting of the trunk

Could this be winter injury in California?

We recently got a call out to a vineyard in the Russian River AVA of Sonoma county to take a look at something weird: unexplained splitting of the bark on the rootstock portion (O39-16 was the most affected) of young vines. This splitting appeared like a “zipper” almost, leaving the wood underneath completely exposed, sans bark.

This is not just an aesthetic issue. The cracking destroys the cambium, the cells that continually reproduce the xylem and phloem. The vine is essentially partially girdled, so an affected vine will look normal for a couple years but sugar transport from leaves to roots will be impaired. In fact, the canopy may even look better in girdled vines verses ungirdled vines for a little while because of this situation. I wouldn’t expect a vine split in this way to ever fully recover.

So what caused this?

This looks like crown gall caused by the bacterium Agrobacterium vitis. It’s one of the few bacteria that attacks grapevines. You can see the tumor-like globules near the graft union and up and down the “zipper”.

Now crown gall is usually something you see in cold climates, where extremely low temperature forms cracks in the woody tissue (usually close to the ground). The bacteria, which is endemic in most vineyards, then attacks the unprotected tissue and proliferates.

The swollen, bubbly area around the split also is made of callous tissue formed as part of the vines wound response after cold injury.

But…we’re in Northern California

Right? This is the weird part. It’s rare that we ever get temperatures low enough to cause winter damage in Sonoma County. But then again, that is a question of the vine’s cold hardiness level.

I am so excited to find an issue with cold hardiness here in sunny California! Not because it’s fixable, (Sorry Mr. Growerman), but because I did my master’s thesis in Washington on cold hardiness and have since found zero reason to even mention it since moving here. Just looking for the silver lining in this matter.

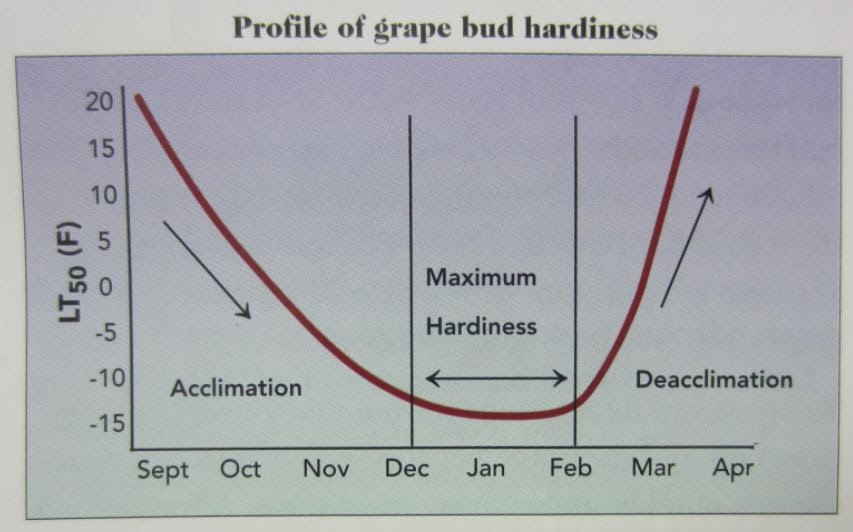

Cold hardiness refers to the vine’s slow acclimation to lower and lower temperatures. This process begins with periderm formation (the green shoots turning brown and woody) and vascular occlusion of the buds. Then vine cells accumulate solutes, which allows water in the cells to “supercool”, meaning that they can withstand temperatures below 0°C without solidifying and instantly killing the cell. To be fair, much winter injury seen results from tissue dehydration, but that is not what causes the cracking and subsequent infection seen in this vineyard.

A vine’s cold hardiness accumulates rapidly as the vine experiences nighttime temperatures between 0°C and -5°C. Vines in cool regions can reach as low at -15°C for Vitis vinifera around mid-winter. American vines, and hence rootstocks bred from them, have different cold hardiness thresholds. Vitis riparia can go as low as -40°C, whereas Muscadinia rotundifolia suffers severe injury at around -12°C. Most of the damage seen in this vineyard was on vines grafted onto O39-16, whose parentage includes M. rotundifolia.

These low thresholds assume that the vine has accumulated cold hardiness. Here’s where I think the main issue lies in this case…

The first issue is that this vineyard experienced a cold snap very early in November 2020, reaching temperatures as low as 25°F (-4°C). Even in cold regions, an early cold event can catch the vines before they’ve had a chance to reach their typically deep cold hardiness levels.

The second, and probably most important, issue is that this vineyard has persistently very moist soil, and continued irrigation for replants has kept it that way. Keep in mind that periderm formation, the first step to dormancy and cold hardiness, is triggered in part by abscisic acid (ABA) hormone in the drying roots. This is why during dry years we normally see such good wood maturity. In early September if this year when we examined this vineyard the shoots were still very green. Green tissue will suffer cold injury at any temperature below 0°C. While the rootstock is already woody, I can’t imagine it had time to accrue much cold hardiness given the state of the canopy (presuming it was in a similar state last year at this time).

Conclusion/What can you do?

There are products you can use against A. vitis. In the event of a serious cold snap, you can use the same fans and sprinklers one would use during frost season, as long as the frost is radiative (i.e. no wind) and not advective (i.e. windy). I believe the real take home is to do what you can to ensure your vines harden off before winter. If vines are still looking green much past August, you may be overwatering. This is true even for young vines, which people especially tend to overwater. Cut back irrigation on young vines starting in late August or early September to encourage them to “harden off”.

Do any of you have experience with winter injury? Tell us about it in comments or via email!

Citations

Keller, M. (2020). The science of grapevines. Academic press.

Martinson T., “Grapes 101: How Grapevine Buds Gain and Lose Cold-Hardiness”, 2021 Cornell University.

Putnam M., Oregon State University Plant Clinic (2006) in Smith D., Oklahoma State University, “Crown Gall of Grapes”, Grapes (blog), 2021 Extension Foundation, https://grapes.extension.org/crown-gall-of-grapes/

“Agrobacterium vitis”, 2021 TaKiMo Agriculture, https://takimo.net/EnHas_BagKokUru.aspx.