Breaking down frost protection

If you can't get out of it, get into it

Frost season was particularly brutal up and down the West Coast this year. With continued early springs brought on by climate change (or the chem trails…eyeroll) it looks like this may be something we just need to get used to.

So I thought I’d break down a few things about frost. As Sun Tzu once said,

You must know your enemy and know yourself

…or something like that. Perhaps Sun Tzu was talking about viticulture or perhaps…you know…not.

Two kettles of fish

Radiation Frost

This is what we’re used to seeing in California. Low-lying areas are where cool air pools. As you move up the slope the temperature starts to rise. This is called the “inversion” because it’s an inverted relationship to the one you normally see where the higher you go up in the mountains say, the colder it gets. A strong inversion, or a rapid increase in temperature as you go up, is actually better because it makes frost fans more effective.

Advection Frost

Advection frosts are considerably worse than radiation frosts since they are usually caused by a cold dry wind. Frost fans are useless since the air is just as cold high up as at canopy level. While these events are rare in California’s wine regions, we did see some of this damage this year. The best defense in these cases are sprinklers, but in general they are much harder to protect against.

Your biggest fan

If you deal with radiation frost and have a nice unobstructed vineyard with gentle slopes, there’s no reason to use anything but wind. They do tend to fail when you have a lot of banks and riparian areas that trap cold air. Fans work if you have a place for the cold air to drain. If you’re blowing it into a wall of trees or up a hill, it’s just going to come back. You may be doing more harm than good.

Sprinklers and the importance of dew point

When water melts or evaporates, it lowers the temperature. This is why you feel cold getting out of the shower or how the canopy of your vines feels nice and cool. Breaking the bonds that hold water molecules together requires energy. When the opposite happens, i.e. water condensing or freezing, the opposite happens. laten heat is transformed into sensible heat (what you measure with a thermometer).

It may seem rather counterintuitive to actively freeze your vines to keep them from getting frost damage, but essentially that energy produced by freezing water is what is keeping those fresh little shoots and leaves safe. But temperature isn’t the only factor to take into consideration.

Dew point is the temperature at which water in the atmosphere condenses and creates dew. At that moment the same amount of water is condensing as it is evaporating. Dew point is a factor of temperature and humidity. It takes less water to saturate cold air than it does hot air.

The art of using sprinklers for frost protection

In order to accurately protect against frost, you need to start using your sprinklers before you reach the critical temperature that causes damage. But how far ahead of the game do you have to be? It’s not like water is scarce of anything…

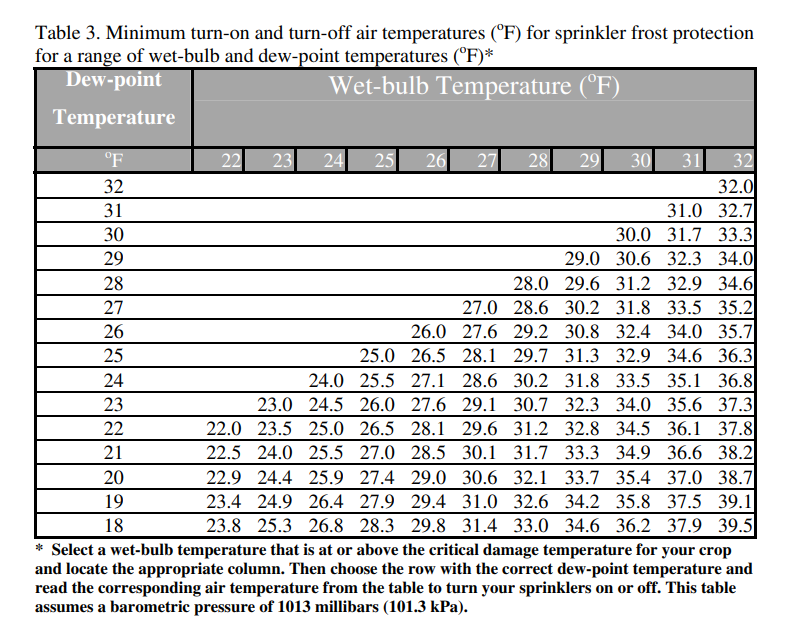

Below is a table that outlines when to turn on your sprinklers taking dew point into account. Pick a Wet bulb temperature that corresponds to the critical temperature at which you want protection for your vines, say 32° (or lower if you’re protecting against winter kill). Then select your dew point. Where those two fields meet is the temperature at which you want to start your sprinklers.

The amount of water you apply matters

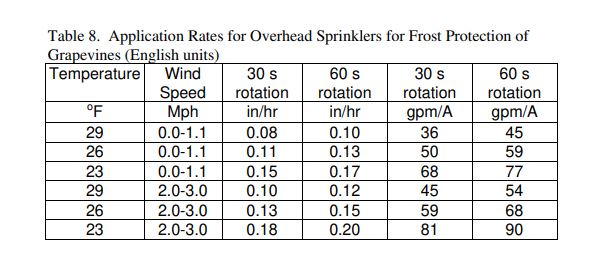

The goal of rotating sprinklers is for water to hit plant tissue, freeze (temperature goes up), and then get hit with another blast of water before it has a chance to evaporate (temperature goes down). Generally, you want the rotation rate to be at most 60 seconds. The shorter the better.

This table takes wind into consideration as well.

The best way to determine if your sprinkers are really protecting your vines is to check for a mixture of liquid and ice in the wetted area. This means that the application rate is enough. If the frozen water appears milky white, it is freezing too fast and trapping air inside the ice. This will do more damage than no protection at all. Sometimes the weather can be just too harsh for sprinklers. The best thing to do is test this out during dormancy or post-harvest, when you can afford to make adjustments.

Other things to consider

Have you ever seen that video of the guy slamming a bottle of ice-cold purified water on the table and the whole thing freezes instantly before your eyes? It’s pretty cool…no pun intended. The reasoning behind it is that pure water can get really cold (supercooled) before it will solidify. That solidification is usually caused by a “nucleation event” that starts of the chain reaction. In the case of the water bottle trick, the nucleation event is the vibration after it’s bonked on the counter. In the case of grapevines, it’s usually bacteria.

This is why treating with copper-based fungicide can help to prevent cold damage. Alternatively, you can use competitive non-nucleating bacteria. I would still recommend getting a frost protection system if you live in a place that suffers frost often.

A worthy investment

Hopefully this frost season didn’t catch too many of you off guard. If it did, you should consider dialing in your frost protection system. We may be in for more of a wild ride in years to come.

Citations:

Snyder, R. L., & Davis, C. A. (2000). Principles of frost protection. Long version–Quick Answer FP005) University of California.