It could be worse...

We are wrapping up a particularly hot July. The last time I had to write about heat stress was 2022, so this year seems to be making up for 2023’s persistent coolness. We all remember 2022. We had a couple hot days in late June that did quite a bit of damage in some vineyards. Then in late August, the sun parked itself right on top of California for three weeks, frying everyone’s hope of a decent harvest.

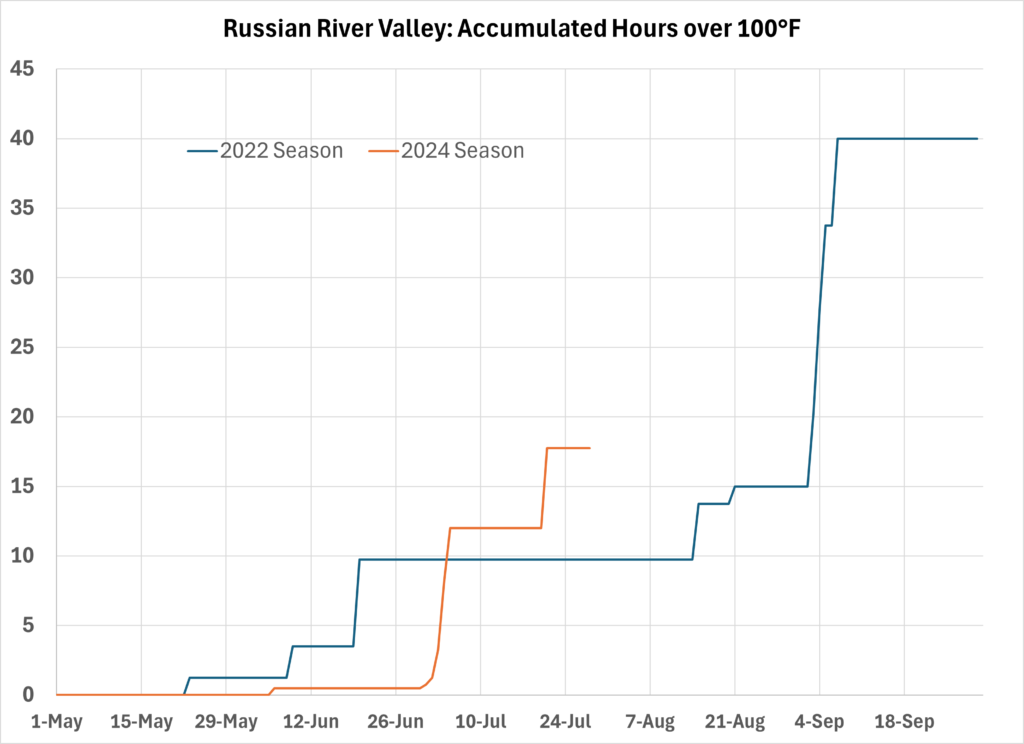

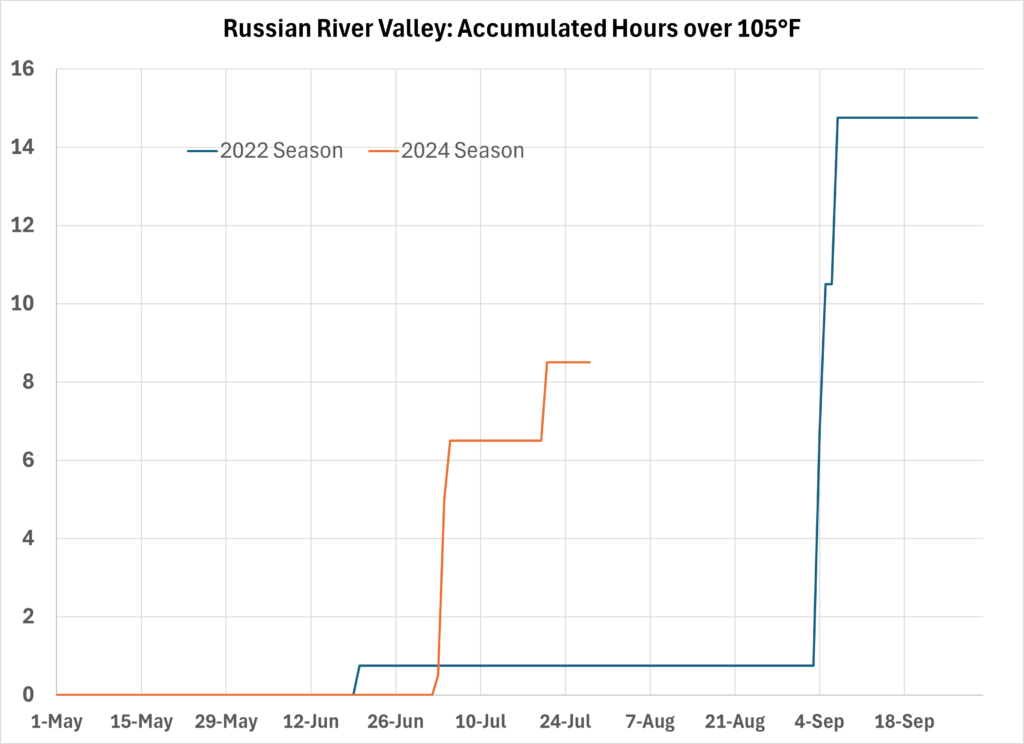

This year, the heat has come earlier and hasn’t quit. One measure Mark Greenspan and I like to look at is amount of time temperatures exceed 100°F and 105°F thresholds. Anything over 100 usually slows down vine growth and metabolism. Anything over 105 causes serious damage.

Here’s a comparison of 2022 and 2024 so far in the Russian River Valley

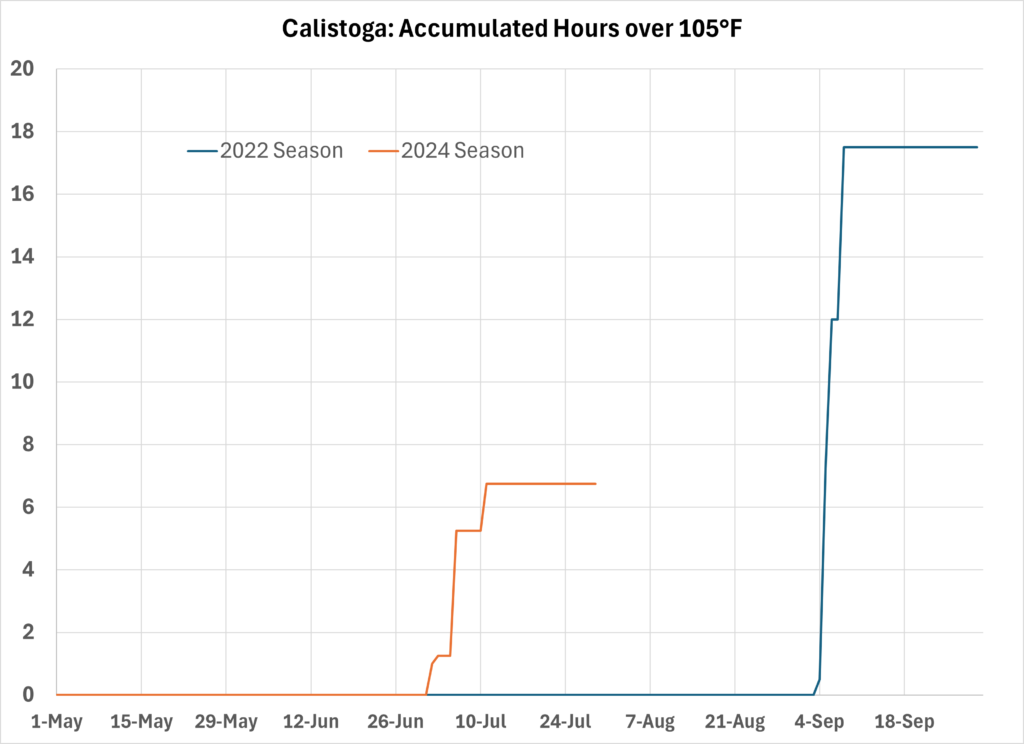

And here’s Calistoga…

At least in Calistoga, 2024 is just a shifted version of 2022.

Now, these are ambient air temperatures. Fruit exposed to full sun can be as much as 15°C (27°F) over ambient temperature, which we initially found hard to believe, but there are numerous studies indicating this. Many of you got there this month. Some growers have experienced complete crop loss due to sunburn and shrivel. Tissue temperatures above 50°C (122°F) causes oxidative stress and cell death leading to the telltale signs of sunburn. This kind of extreme heat can also denature the proteins responsible for fruit maturation. This fruit may look alright immediately following the heat event, but it will never catch up in terms of color or maturity. We’ve all seen those pink berries that never really fully color up. The good news, if there is any, is that this fruit can be easily eliminated in late-season thinning passes as it looks very different from unburned fruit. I recommend leaving it as a physical barrier that can protect your remaining fruit until the survivors are fully through veraison.

But what about this remaining fruit…if you have any. Unexposed, shaded fruit is usually on par with ambient temperature. Ambient temperature is still really hot. What does an early and prolonged heat wave mean for the surviving vintage?

Heat and timing

If you’re going to get heat, pre veraison/lag phase is the best time to get it. Weston et al. (2010) out of Australia looked into the effects of heat (40°C or 104°F) at different stages of growth. They found that heat events that occur between fruit set and veraison have very little effect on yield or quality. At this point, berry growth is from cell division and later cell expansion driven by water influx from the xylem. Photosynthesis at any stage of growth is dramatically reduced by heat events and may take over a week to recover back to full capacity. Pre-veraison berries are less of a sink at this point and so are less affected by the low sugar transport caused by lower photosynthetic rate.

Veraison brings about big changes in the grapevine’s physiology. The vine shifts focus from growing vegetatively to growing reproductively. Grape berries become the major sink of sugars produced via photosynthesis, which they store as opposed to using for their own metabolism. At this point, the berry’s cells initially expand for the second time during development, which is largely affected by water brought in actively (enzyme driven sugar unloading an osmotic water movement) via the phloem as opposed to passively via the xylem (which is more simply biophysical).

Weston found grapes that received heat treatments at veraison and mid-ripening were shown to be smaller and accumulated sugar until 25 brix (veraison treated) and 27 brix (mid-ripening treated) before ultimately declining. This is most likely due to diminished photosynthesis that fails to keep up with the sugar demands of a ripening grape. In addition to the obvious burning and shriveling, this is why so many growers saw ripening stagnate in 2022.

Another study out of Australia (Barril et al. 2019) looked at the effects of a pre-veraison (pea-sized and bunch closure) heat event on phenolics and acidity. While they saw that there was an immediate effect on tannin accumulation, any significant differences between heat-treated and control disappeared by harvest. They also found that the heat-treated vines had significantly higher malic acid at harvest, which in a hot year can be a plus.

Thermotolerance

High temperatures occurring prior to veraison might also make the vines more resilient in the face of post-veraison heat spikes. Vines exposed to high temperatures develop heat shock proteins, special chaperone proteins that essentially protect important enzymes from denaturing (unfolding) or newly formed enzymes from folding poorly and losing functionality.

Wample et al. (1995) studied heat sterilization techniques for crown gall. They found that vines exposed to 40°C (104°F) for a few hours and then given time to recover were then able to withstand a water bath of 50°C (122°F), which is normally lethal for grapevine tissue.

Most studies focus on leaf tissue, which is important given that a lot of the problems with late-season heat shock seem to stem from depressed photosynthesis not being able to produce enough sugar. More resilient leaves means more resilient ripening patterns. There has been at least one study (Shrader et al. 2001) on similar heat shock proteins synthesized in the skins of apples. This indicates that grapes themselves may be able to build thermotolerance, although it’s unclear how long lasting the effects are.

Irrigating to prevent heat stress

We get calls all the time in anticipation of a heat wave asking how much water to apply. Our general response is, if it makes you feel better, irrigate. But don’t expect to avoid the effects of heat stress by watering.

Vines can cool themselves via transpiration (i.e. water evaporating from the stoma on the underside of the leaf). Heat stress, however, has been shown to close stoma in response to reduced photosynthesis. This means that transpiration is less effective as a cooling method during high temperatures.

Green fruit, while it does technically have stomata initially, the stomata quickly become non-functional and so berries transpire very little compared to leaves. Berry transpiration is significant, but not via stomata and therefore, is not affected by vine physiology or water status. Watering is not going to save your fruit, especially if it’s exposed.

Water stress can aggravate heat stress and the two are at least loosely linked in that water stress can be elevated by high vapor pressure deficit (VPD). High VPD can lead to leaves producing their own abscisic acid (ABA) and by lowering water potential (i.e more stress). That being said, most places we monitor were not water stressed at the beginning of July and many continued to not be water stressed even with the heat. This doesn’t mean that heat stress didn’t wreak havoc. It just means that watering excessively wouldn’t have fixed it.

Don’t be that guy

I’ve had at least one grower tell me that their method is to saturate the soil so much that the evaporative cooling of the soaked ground lowers the fruit zone temperature. I cannot imagine how much water you need to apply to bring about a significant temperature drop.

If you plan on using evaporative cooling to mitigate heat stress, you should apply it where it counts. Misters and microsprinklers apply that water directly the canopy or fruitzone. Better yet, they don’t need to wet the canopy or clusters to be effective. By mist particles evaporating while suspended in the air, they cool the air. Misters are preferred as they emit around 1 gallon/hour, which is on par with drip emitters used in irrigation. They do clog easily, so having hard water on site may prove challenging. Microspinklers have a higher output, but do not need to be run continuously and are spaced out further than emitters. Since they wet foliage, they can and should be turned off periodically to avoid excessive humidity and potentially even disease. You can read more about evaporative cooling here.

Conclusion

This year is a hot one so far. Heat waves always do damage, but getting heat early is likely to have a minimal effect on whatever vintage we manage to pull out of this.

We’ll just have to see what the rest of the season throws at us.

Citations

Morrell, A. M., & Wample, R. L. (1995). Thermotolerance of dormant and actively growing Cabernet Sauvignon is improved by heat shock. American journal of enology and viticulture, 46(2), 243-249.

Greer, D. H., & Weston, C. (2010). Heat stress affects flowering, berry growth, sugar accumulation and photosynthesis of Vitis vinifera cv. Semillon grapevines grown in a controlled environment. Functional Plant Biology, 37(3), 206-214.

Ritenour, M. A., Kochhar, S., Schrader, L. E., Hsu, T. P., & Ku, M. S. (2001). Characterization of heat shock protein expression in apple peel under field and laboratory conditions. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 126(5), 564-570.

Gouot, J., Smith, J., Holzapfel, B., & Barril, C. (2019). Single and cumulative effects of whole-vine heat events on Shiraz berry composition. Oeno One, 53(2), 171-187.